Flight Ops

COVID-related constraints and concerns have led to significant changes to flight operations. While it may be some time before operations can be considered "normal", guidance provided in this section offers a means for adapting flight operations in the "new normal" of COVID conditions, as well as moving back towards a situation whereby the various flight ops-related SARPs are complied with, even if using alternative means.

The flight operations guidance is grouped under the following headings:

Personnel

The guidance provided in this section addresses aspects related to training, licensing, flight and duty time limitations and fatigue management, and methods for supporting personnel and preparing them for return to work.

Returning to normal crew training, proficiency and recency validity periods

In response to the COVID-19 crisis and the need for an extension to the validity period of the pilot license and associated ratings, National Aviation Authorities have approved globally, for a limited period, alternative solutions to the traditional licensing and operational requirements.

The value of these alternative solutions was clearly to ensure operations when maintaining pilot recent experience was difficult to achieve, the training capacity was limited, and the administrative licensing revalidation process was disturbed. However, as of 31st March 2021, it is expected that the States will not grant any more alleviations.

The following sections offer possible solutions for challenges associated with returning to normal crew proficiency and recency validity periods:

Training Solutions Roadmap (CLICK HERE)

For the restart of operations, States and Operators must be confident that pilots are performing to the adequate performance standards to ensure safe and efficient operations. This Roadmap supports States, operators and training organizations that are managing the end of the training alleviations period. It provides incremental training solutions that reflect the duration of the limited training period and the pilot's operational experience.

Specific Requirements for Instructor-Evaluator Pilots (CLICK HERE)

In order to manage the training solutions described in the roadmap, operators will need to have a plan to ensure their instructors and evaluators (IE) are fully recent and competent. This section provides additional information to assist with the process of IE refresher training.

Developing a COVID-safe plan for the purpose of training or Pilot Proficiency Checks (PPCs) using FSTDs in another State or region

This section builds on the Public Health Corridor concept to enable training and PPCs to be conducted in the FSTD facilities of a training organization in another State or region.

During the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary alleviations allowed extensions to the validity period of ICAO Annex 1 and Annex 6 standards related to pilot training, checking and recent experience. As an example, in the case of commercial air transport operations, ICAO SARPs require pilots to complete regular proficiency checks (PPCs) twice within any one-year period (see Annex 6, Part I, Section 9.4.4.1). Pilots are not permitted to fly if these checks cannot be completed.

However, to maintain an acceptable level of safety, validity periods for pilot licences, medicals and certificates cannot be extended indefinitely. Any extensions should only be allowed having considered the associated risks and mitigating measures through the operators' SMS and, operational requirements. Additionally, for the continuation of operations following extended periods of reduced flying, or restricted movement of flight crews, there is a need to plan for a return to pre-COVID ICAO SARP compliance to ensure an adequate level of safety is maintained. This document focuses on the restoration of compliance related to flight crew training and PPCs.

Pilot training or PPCs are predominantly carried out in Flight Simulation Training Devices (FSTDs). Some States do not have "in-country" FSTD training facilities and as such pilots have no option other than international travel in order to carry out their PPC's. COVID-19 has restricted travel to the extent where pilots have been unable to travel to their usual "out of country" FSTD facilities. In the majority of cases inbound passengers, both airline crew and the traveling public, are subject to quarantine requirements on arrival, making the process operationally and economically unviable from an airline perspective.

This following sections provide guidance on the development of a COVID Safety Plan to enable travel for the sole purpose of pilot training or PPCs in FSTD facilities provided at an approved training organisation (ATO) in another State.

Note: Throughout this guidance reference is made to travel to "another State", where State in this context is referencing another country. However, it is also necessary to consider that many countries have internal region and/or territory border travel restrictions. In addition, some local region restrictions may apply. It is intended that this document provides the basis upon which cross border travel, whether it be international, regional, or interstate, is facilitated using strict travel protocols detailed in this document as mitigating measures to prevent the transfer of COVID-19.

Planning and monitoring tool (CLICK HERE)

This tool supports States and organizations in anticipating and planning for mitigations as a result of deferred certificate validity renewals stacking up.

Meeting medical aspects of crew licensing requirements

Meeting flight dispatcher training needs

Fatigue management and returning to compliance with national FDTL regulations

COVID-related constraints and concerns have resulted in many operators being unable and/or unwilling to schedule normal rest periods for crew down route. Operators have sought to avoid onerous State restrictions to their operations and/or exposing their crew to increased risk of infection or having them subjected to invasive testing or quarantining. This has led to extensions well beyond established national flight and duty time limitations (FDTLs).

The world has now had time to adapt to the challenges that Covid-19 has presented. States are protecting their citizens with screening, quarantine and air traffic passenger reduction policies. Often these policies change at short notice, but this very changeability is now an expected situation. Airports and airport hotels are developing Covid-19 secure procedures and aviation activities are continuing, albeit at greatly reduced levels in many cases.

While the continuation of international operations remains essential, "normal" international operations are not urgent to a level that justifies the increased risk associated with significant extensions to FDTLs. Even the continued use of relatively minor extensions in the more-demanding context of COVID- operations (e.g. potential job loss, fear of infection, changed operational environment) can result in crew experiencing cumulative fatigue - with likely implications for their performance.

Operators now need to return to managing fatigue within existing FTDLs (or using an approved FRMS) and take the time to prepare for an increase in operational activity in the medium term. Regulators need to ensure that the management of overall fatigue risk and the safety of operations is maintained, taking into account the basic fatigue-related scientific principles and recognizing the extra burdens associated with operating in COVID-19 conditions.

This webpage provides guidance for regulators to support operators in returning to "normal" scheduling limits and practices while managing the fatigue risks during the transition back to more "normal ops" under the following headings:

1. Applying the basic scientific principles to manage fatigue risks within the prescribed limits

This section explains what a prescriptive approach to fatigue management entails and identifies the 4 basic fatigue management principles that need to be considered.

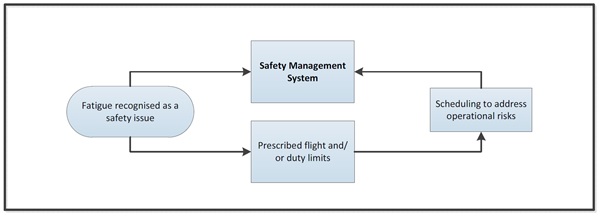

Prescriptive limitation regulations identify maximum work periods and minimum non-work periods for specific groups of aviation professionals. Within these limits, operators must manage their fatigue-related risks as part of their existing safety management processes. The prescriptive approach to fatigue management is summarised in the following figure.

In order to support operators' efforts to identify specific fatigue risks and select appropriate mitigations, airlines should first consider the impact of the four key scientific principles.

These basic principles relate to: 1) the need for sleep; 2) sleep loss and recovery; 3) circadian effects on sleep and performance; and 4) the influence of workload, and can be summarized as:

- Periods of wake need to be limited. Getting enough sleep (both quantity and quality) on a regular basis is essential for restoring the brain and body.

- Reducing the amount or the quality of sleep, even for a single night, decreases the ability to function and increases sleepiness the next day.

The circadian body clock affects the timing and quality of sleep and produces daily highs and lows in performance on various tasks. - Workload can contribute to an individual's level of fatigue. Low workload may unmask physiological sleepiness while high workload may exceed the capacity of a fatigued individual.

- Using these basic scientific principles will assist airlines to identify their contextual fatigue risks both now, and as they increase their operations, in order to develop suitable mitigations.

2. Operating within the prescribed FDTLs

While some airlines may use advanced approaches and have an approved fatigue risk management system, most will be scheduled within the prescribed flight and duty limits and managing their fatigue risks through their SMS processes. This section focuses on the basic expectations of Operators complying with FDTLs.

In recognizing fatigue as a safety issue, ICAO SARPS requires States to establish prescriptive flight and/or duty limitations regulations for aircrew. They should be designed to maintain an acceptable level of safety performance in the majority of situations.

In a prescriptive approach to fatigue management, the operator is expected to schedule within the prescribed limits, according to their specific context and to the risks that generate fatigue within their operation. The effectiveness of their scheduling practices is then monitored as part of their SMS. Through their oversight practices, the State ensures that the operator is managing their fatigue risk to an acceptable level within the constraints of the prescriptive limitations and requirements using existing SMS processes.

COVID-19 requirements within the changing operational environment mean it is even more important that these risks are managed to an acceptable level of safety as airline operations develop into a "new normal" approach.

Operators are still required to:

- retain records of work and non-work periods, including planned and actual work and non-work periods, with significant deviations from prescribed limits and minima recorded;

- publish an individual's work schedules sufficiently in advance to allow planning for work and rest periods;

- take steps to keep changes at short notice to a minimum and to minimize their impact;

- actively manage the assignment of unscheduled duties through operational processes and procedures. The focus should be on:

- minimizing the extent of disruption to the timing of a planned duty;

- providing protected sleep opportunities (prior to, during and after unscheduled duties);

- identifying minimal notification periods for changes to planned duties; and

- limiting the number of consecutive days that they may be subject to being assigned unscheduled duties.

3. Fatigue-related challenges in COVID-19 conditions

This section identifies additional fatigue-related challenges that may be presented by COVID-19 conditions.

COVID-19 conditions both within the State and globally mean that there may be additional fatigue-related challenges when returning to normal operations.

In current COVID-19 conditions, the following present further challenges for managing fatigue-related risks:

The unknown effects of the continuation of other alleviations that the operators may be using (such as extended validity periods for proficiency and medical checks);

Reduced roster publication timelines due to rapidly changing commercial schedules;

Fatigue mitigation options for the pairings and the roster are limited due to lack of flexibility in the reduced aircraft flying programme;

Reduced contingency options;

Restrictions at layover locations affecting rest periods, including hotel issues, access to nutrition, etc.;

Uneven workload distribution between crew members due to a limited pool of pilots for reasons such as recency and currency or due to reduced number of available bases;

Increased workload placed on training captains as more pilots return to flying requiring training for recency or currency;

- Rostering to maximum or minimum flight and duty limits and the potential for further roster disruption when delays are encountered;

- Failure of pre-flight reporting times and post-flight duty to take account of the additional time needed for extra airport and company procedures;

- Short notice changes and disruption to rostered duties because of rapidly changing State restrictions;

- Airport congestion due to COVID checks creating on time performance issues;

- Additional workload and fatigue-related issues with regard to the wearing of PPE with Cabin Crew & additional passenger procedures whilst on board;

- Unexpected delays or extended turnaround times due to new COVID-19 procedures;

- Difficulties associated with ensuring availability and access to adequate meals for crew during the flight period;

- Altered and more time-consuming aerodrome security arrangements secondary to COVID-19 conditions.

- Changed pairing construction, different routes and to unfamiliar airports, and changes from passenger to cargo-only flights.

- Crew hesitancy to report fatigue-related hazards when there is an over-supply of pilots.

These conditions could mean the State's prescriptive regulations, including maximum flight and duty limits and minimum rest periods may not be sufficient to maintain an acceptable level of safety due to the unknown and rapidly-changing environment. It is imperative that operators look to managing their unique operational safety risks using their SMS.

4. Managing the additional fatigue challenges in COVID-19 conditions

This section outlines things that Operators can do to address the additional fatigue-related challenges.

In recognition of these additional challenges on a State's prescriptive FTDLs, consideration of the following areas on crew fatigue should also be demonstrated by the operator and reviewed during oversight activities. Operators should:

- develop planning buffers to prevent scheduling up to the limits of the prescriptive requirements;

- risk assess the impact of extended recency and proficiency checks, medicals and other alleviations on fatigue;

- closely monitor of any trends in the use of pilot discretion and take steps to minimize its use;

- monitor and seek to mitigate disruption to aircrew's planned duties, especially at short notice;

- share workload across available crew, particularly management pilots and aircrew trainers who may also be working in the simulator;

- have a process for monitoring the use of controlled rest in the flight deck (when legal under State regulations) to prevent it becoming seen as planning tool instead of an emergency procedure;

- include the importance of "crew health/fatigue checks" as part of pre-flight briefings;

- take account of increased times at airports (queuing and COVID testing) in pre and post FDP duties;

- assess layover conditions to protect crew's physical and mental health;

- assess the impact of organizational changes and restructuring, such as redundancies and the potential effect that this may have on crew and their ability to fully rested and fit for duty;

- actively encourage crew to report fatigue-related occurrences and concerns they may have;

- assess the additional workload associated with the wearing of PPE and other additional passenger procedures on cabin crew.

Finally, all airlines are reminded that they need to track the performance of their fatigue management approaches through a set of assurance activities. Therefore, not only do they need to have enough flight and cabin crew, but they also need to have sufficient competent office-based personnel to carry out the necessary support activities for effective operational fatigue management.

5. Approving variations to existing State FDTL regulations

It is recognized that rare situations may still present themselves that necessitate international flights flown by crew members under approved extensions to FDTLs. This is provided for in Annex 6, Part I SARPs. This section provides guidance to regulators on approving variations to FDTLs.

ICAO SARPs allow for States to offer some limited flexibility to the service providers complying with the prescribed limits by way of variations. This means that in very limited circumstances and for limited periods of time, a State may allow minor variations to the prescribed limits. Such approval would permit an operator to schedule outside of the State's flight and duty limitations, without the need for the operator to develop a full FRMS. It is the State's responsibility to avoid the approval of variations to the FDTLs that meet operational imperatives in the absence of a risk assessment. The approval process of an operator's risk assessment in support of their request for varying from State FDTLs is discussed in detail in the Manual for the Oversight of Fatigue Management approaches (Doc 9966).

COVID-19 conditions already present additional challenges to crew, even when they are operating within prescribed FDTLs. Further, an operator may also be using alleviations, such us extensions to medicals, recency or training requirements, to enable operations in COVID-19 conditions, and the possibility of compounded risks with extended FDTLs should also be recognised and addressed. Therefore, where requests to operate outside of flight and duty limits are sought, the regulator will need to approve their use based on an operator providing a risk assessment that clearly identifies and addresses ALL associated risks, including those related to fatigue. When evaluating an operator's risk assessment and the proposed mitigations to determine whether approval will be granted, everything is proportionate to the level of safety risk posed by the variation being requested.

Given the extra challenges of operating in COVID-19 conditions, answers to the following questions are of particular relevance when a regulator is evaluating an Operator's risk assessment to support its temporary use of minor variations to national FDTLs:

- Does the operator identify a method to assess cumulative fatigue on the flights and duties associated with the variation and the full roster pattern?

- Where bio mathematical models are used by the operator to predict fatigue levels associated with the proposed flight and duty variation, does the operator clearly understand its limitations? Was operational experience also used to develop the safety case for these flights?

- Is there evidence of crew support and involvement in the development of the safety case? For example:

- Is there evidence that the operator has considered the impact on crew performance of factors such as confinement to room on layover, stress, etc. within the safety case?

- Has the impact of State restrictions on entry/exit and quarantine of crew members been addressed?

- Does accommodation and transport during layovers adequately protect crew from infection?

- Does the operator identify contingency plans for unexpected and changing circumstances?

- Has the operator identified how it will monitor the effectiveness of the proposed mitigations?

Some of the types of mitigations that a regulator could expect to see in an operator's risk assessment to address these extra COVID-19 challenges are presented in the list below.

Areas for consideration and Possible mitigations

- Route planning

- The report times and flight departure times should reflect a window(s) for optimal crew alertness.

- For multiple sector augmented flights, the sector length must allow for adequate inflight sleep. If the sectors are too short, there might not be adequate opportunity for sleep. If the flight duty period has a long sector followed by short sectors, it can drive greater time awake.

- Revised dispatch criteria are identified to avoid COVID-related issues that might cause undue workload or fatigue.

- Suitable and COVID-safe airports for diversions are identified for either operational or fatigue related issues during the operation.

- Scheduling

- Flight and cabin crews are appropriately augmented as required by the safety risk assessment for each rotation.

- Pre- and post-flight rest periods enable the crew to be fully rested prior to operation and allow for a full recovery after the operation. Additional pre-trip rest to ensure fitness for duty, and post-flight rest after the specific operation to reduce cumulative fatigue on subsequent duties.

- Rosters have been adjusted to avoid critical phases of flight during the window of circadian low (WOCL).

- The use of the same crews for consecutive variation operations is avoided as fatigue can accumulate across a roster pattern, not just in relation to a single trip.

- Scheduling adjustments are made to accommodate operating the varied FDTLs within the weekly / monthly limits for duty, rest and flight time.

- On time performance is monitored and changes schedules or pairings are made where there is evidence that the plan is not working as intended.

- Rest periods and facilities are suitable to enable the crew to be well rested and fit for their rostered duties when operating under the variation.

- Crew feedback is sought to ensure the mitigations are and remain suitable for the operations using the variation. Where necessary changes to the mitigations or the variation is made as a result of this feedback.

- Crew preparation and support

- Processes are identified for pre-notifying crew for extended duty operations and for ensuring reserve/standby crew are aware of potential for being called in to operate the variation.

- Fatigue awareness and management briefings, specific to the variation, are developed and provided to crew sufficiently ahead of commencement of operations.

- Public health corridors from aircraft to airport hotel facilities are provided to limit transit time and challenges generated by the Covid-19 situation.

- In-flight fatigue management

- Methods to maximise in-flight rest time allocation for all crew in support of optimising crew alertness are identified. Emphasis should be placed on having the most rested crew members in control seats (and at crew stations / assigned exits for cabin crew) during the critical phases of flight.

- Where crew are expected to obtain in-flight sleep, in-flight facilities must be in line with the fatigue-related science and adequate to facilitate sleep. Provision of appropriate facilities for on-board sleep and protected cabin spaces (away from passengers, cargo) to support rest.

- Arrangements have been made to ensure nutritional requirements are suitable and are readily available for the duration of the duty.

- Crew are provided with the flexibility to allocate rest and operational duties on the day to manage actual sleep / alertness needs of the crew.

- There is a method to monitor the use of controlled rest and ensure it is used in accordance with Fatigue Management Implementation Guide for Airline Operators (see further guidance below).

6. Extreme extensions to flight duty periods

Ultra-long range (ULR) flights have been operated safely for many years but under carefully designed conditions and with scientific input and regulatory oversight. This section aims to assist regulators and operators understand the safety implications of flight duties where the normal layover between long-haul flight sectors is removed, resulting in duty periods beyond those previously operated (e.g. longer than approx. 19 hours).

The COVID-19 pandemic has led some operators to seek regulatory approval for extreme extensions to flight duty periods in order to remove the need for a layover. Operators seeking such approvals may not have had experience in conducting ultra-long range flights and mitigating the associated fatigue-related risks based on scientific principles, nor of managing fatigue risks using an approved FRMS. In all cases, it is the regulator's responsibility to determine whether an acceptable level of safety can be maintained by the operator while they are in use.

It is therefore particularly important for regulators to carefully weigh the need for extreme extensions to flight duty periods with the associated safety risks and the operator's ability to manage those safety risks, given that as the pandemic period progresses, there are fewer circumstances demanding exceptional operational responses.

The following information has been put together by researchers at the Sleep/Wake Research Centre, Massey University to assist regulators and operators assess the safety implications of operations that would demand extreme extensions to flight duty periods. It summarises current scientific knowledge related to very long duty periods and is based on their previous research on ultra-long range (ULR) flight operations and the research of others on sleep and fatigue in flight.

- What we know about very long duty periods

- Ultra-long range (ULR) flight operations have been conducted safely since 2004, with the operations that have been studied having the following fatigue mitigations in place:

- Operations are considered as a city pair (the outbound and return flight) even if only one sector meets the requirements for ULR flight.

- Flights are operated by a fully augmented crew, recommended to include an additional Captain and First Officer to allow one crew at a time to obtain in flight sleep.

- Typically, one crew is designated in advance as the operating/flying crew (who conduct the take-off and landing phases of flight) and the other crew are designated the relief crew;

- There are protected days off prior to and following a ULR trip (normally 2-3 local nights prior and 3-4 local nights following the duty) to allow crew to be rested prior to departure and recover following the duty;

- There are normally two scheduled in-flight rest breaks per crew, with a longer rest break scheduled for a more biologically favourable time and the landing crew having the second and fourth rest break (the last break closest to the descent and landing phase of flight);

- The regulator has approved the ULR operation and the operator has an approved Fatigue Risk Management System that at a minimum covers the ULR operation. This ensures on-going fatigue monitoring;

- Flight crew receive training in fatigue science and its application to long flights/duties and there is route-specific guidance material developed.

- Sleep

- The amount and quality of sleep that crewmembers can obtain depends on where their sleep opportunities fall in the daily cycle of the circadian body clock, which promotes sleep at night in the time zone to which it is adapted (known as the 'biological night'). It also facilitates sleep in the afternoon nap window in that time zone.

- Sleep obtained during in-flight rest opportunities is shorter and of poorer quality than sleep obtained by flight crew on the ground.

- Flight crew are more likely to attempt sleep, and they get more sleep, when an in-flight rest opportunity is during their biological night.

- On longer flights, flight crew obtain more in-flight sleep. This is because they have more opportunity for sleep but the amount of sleep obtained will also depend on the time of day of the flight relative to the crews' circadian body clock time.

- Shorter in-flight sleep opportunities are generally used less for sleep than longer opportunities (flight crew may use shorter rest periods for rest or meals instead of sleep). However, shorter rest opportunities are also often scheduled for a less ideal biological time.

- The type, design and location of crew rest facility influences in-flight sleep:

- Flight crew report preferring to sleep in rest facilities with lie flat bunks separated from the main cabin, due to noise, comfort and privacy.

- Flight crew report that noise, comfort, humidity, temperature and timing are important for their sleep in crew rest facilities.

- Flight crew often plan for their in-flight rest by changing their pre-flight activities, thus they prefer to know ahead of time what the in-flight rest break pattern will be.

- The angle of the seat in which a person is sleeping makes a difference to the amount and quality of sleep obtained. A more reclined seat results in more sleep and better quality sleep.

- By top of descent, flight crew with longer duty periods have had less sleep in the last 24 hours compared to flight crew with shorter duty periods.

- The amount of sleep obtained in the 24 hours prior to an inbound flight is greatest when duty start time allows for the inclusion of a full domicile night time period at the layover.

- How flight crew feel and function

- Flight crew report being sleepier, more fatigued and are slower on a reaction time task at the end of a flight compared to the beginning of a flight.

- Flight crew feel less sleepy and fatigued after an in-flight sleep compared to before.

- Flight crew are generally less sleepy and their performance is faster after longer flights compared to shorter flights due to a combination of the timing of the flights and longer in-flight sleep opportunities.

- Flight crew often feel sleepier and more fatigued at top of descent if they have been awake for longer.

- Time of day is a key factor in determining how sleepy and fatigued flight crew report feeling and how fast they are on a reaction time task at top of descent (they are more sleepy and fatigued and slower at responding during the biological night and early morning).

- In short haul flights, additional sectors increase ratings of fatigue but this also depends on the length of the duty, time of day and number of consecutive duty days worked.

- Cabin crew

- Many of the points noted above will also apply to Cabin Crew. However, they normally operate with slightly more crew rather than augmented crew. They also do not have the same opportunity for in-flight sleep and the rest facilities they have access to may be less conducive to sleep.

- Ultra-long range (ULR) flight operations have been conducted safely since 2004, with the operations that have been studied having the following fatigue mitigations in place:

- What we don't know about very long duty periods

- How well flight crew sleep in flight when they are positioning rather than on duty. This is likely to depend also on the facilities available for sleep and the time of day that sleep can occur.

- How well flight crew sleep when a rest opportunity is on-board the aircraft, but the aircraft is on the ground (such as during a turnaround).

- How the functioning of flight crew differs across multiple flights within a long duty period compared to their functioning across a single long flight within a long duty period.

- What the functioning of flight crew is like by top of descent when the duty period is longer than about 19 hours.

- How long the relatively small amount of reduced-quality sleep obtained in flight can sustain the functioning of flight crew. That is, how long is too long for a duty period? Is there a point at which functioning rapidly declines? This will likely depend on both how long a crewmember has been on duty AND the part of the circadian body clock cycle he/she is in (the biological time of day).

- Summary

- ULR flights have been operated safely for many years but under carefully designed conditions and with scientific and regulatory oversight. However, scientific knowledge is currently lacking on how long short and disrupted in-flight sleep can sustain the safe functioning of flight crew. Nevertheless, from a scientific perspective there is reason to expect that very long duties with multiple long sectors where crew may "position" on one sector and are not provided with a layover, potentially pose elevated fatigue-related risk.

7. Further guidance

- Manual for the Oversight of Fatigue Management Approaches (Doc 9966), Second Edition, Version 2 – with particular reference to Section 4.2.3.

- IATA/ICAO/IFALPA Fatigue Management Guide for Airline Operators

- ICAO's Fatigue Management website

- Webinars:

Extending Flight and Duty Limits for COVID-19 "Special Ops"

This webcast discusses the risk and possible mitigating strategies of flight duty extensions, providing advice to airlines applying for variations to FDTLs and to regulators who approve these applications.

Managing Fatigue in COVID-19 "Normal Operations"

This webcast provides insight into managing fatigue risks introduced by the operational changes during COVID-19 conducted within national FDTLs, and how data-driven decisions are a key component of overall flight safety.

Managing risks to flight crew performance

Given the centrality of human performance to the performance of the global aviation system, factors that may impede an individual's ability to perform safety-related duties must be managed carefully and effectively. Such factors have only increased in COVID-impacted conditions, because of:

- the effects on individual mental health and well-being (see ICAO Electronic Bulletin 2020/55); and

- extensive and rapid changes to the work environment as a consequence of:

- The need to maintain physical distancing and to wear personal protective equipment;

- Meeting new requirements for quarantining, sanitization, hygiene and health status checks;

- Diminished availability of human resources due to, for example, restricted work access for vulnerable people and personnel on furlough.

This section focuses on the management of operational safety risks posed by the challenges of flight crew working in the "new normal" of COVID-impacted conditions. Guidance is provided under the following headings:

1. HP challenges for flight crew working in COVID-impacted conditions

The following table presents some of the COVID-impacted work conditions that can result in HP issues that have consequences for how pilots perform their duties. When considered separately, each HP issue may not be considered particularly hazardous to operations. However, they rarely present in isolation. For pilots already working in demanding circumstances, it is important to consider how these HP issues may interact, combine and compound, possibly compromising their ability to manage non-normal or challenging operational situations.

For flight crew, the COVID-impacted work environment may have resulted in: | Potential effects on human performance (which may present operational risks): |

|

|

| Fatigue-related issues:

|

| Procedure-related issues:

|

| Fitness for duty-related issues:

|

These conditions mean that it is imperative that operators look to managing their unique operational safety risks related to HP. At the same time, these conditions also mean that operators are less likely to receive the information that they need to be able to monitor and maintain safe flight operations.

For States, it means that the impact of the changes within the complex aviation environment are more difficult to assess and any risks generated as unintended consequences of decisions being made may be missed.

2. Supporting flight crew returning to work after a long absence

COVID-19 conditions both within the State and globally mean that there may be additional challenges when returning flight crew to normal operations.

Where crew have been on furlough, leave or have been non-current for a long period of time, they may experience a feeling loss of confidence in being able to operate in the changed environment. They may pass a PPC and be able to demonstrate that they operate the aircraft during the required procedures but may have concerns about the lack of practice within the day to day environment. Operators should seek to tailor the return to work training and work planning in a way that supports crew as they re-enter flying operations. It maybe that they are given extra time in the simulator or are provided with more than the legal minimum number of flights with a trainer in order to release them back into normal operations. In addition, increased time for flight preparations should be allocated during the first few weeks after a return to duty.

Some personnel may also not feel safe and in control about returning to work. They have concerns about contracting Covid-19, exposing vulnerable family members to the virus, or may have even experienced the loss of a close relative or friend to the disease. Many may have isolated individually or with limited family members and are hesitant to reengage in an everyday routine. Operators need to consider return-to-work conversations with their crew members and make sure that all crew are aware of the support (including peer support programs) available to them to enable crew to return to work confidently.

Some crew may have experienced specific issues associated with wellbeing during lockdown. These could be depression, increased use of alcohol as a coping mechanism or other issues associated with isolation from society. Changes to a flight crew member's health status, in association with decreased access to aviation medical examiner support, can result in increased operational safety risks. Again, operators need to be aware of the potential for these issues and publicize mechanisms and activities to support flight crew to return fit for duty.

3. Mitigations and safety barriers for operators

In order to develop appropriate mitigations and structures to support a return to more normal operations, the operator may need to do more to promote their safety culture in order to build trust and confidence with their flight crew, particularly around some of the non-traditional challenges presented by operating in COVID-impacted conditions. Some key areas to support this are identified below.

Communication lines

While it might be time consuming, keeping crew members aware of how the operator is responding to the challenges of continuing to operate and to rebuild their passenger base means that they remain engaged with the organisation. This is an important element to ensure they provide the airline with safety critical information about the operation and themselves and may mean:

- Providing clear and frequent communication with employees using multiple methods of media in order to reach all the different work groups;

- Offering timely feedback to crew suggestions or hazard reports which have led to safety improvements and changes;

- Using crew member champions to support the communication of operational issues and changes.

Collecting data to support safety management

COVID-impacted conditions have resulted in very different, frequently unexpected and changing flight and duty experiences for crew members. To maintain safe operations in these unique conditions, the operator needs a full understanding of the day to day environment in which the flight crew are having to manage their way through. However, the reporting of hazards and occurrences, particularly any related to fatigue, may drop if personnel are worried about their jobs. Methods used pre-COVID may need to be adapted to enable a complete picture to be formed. For operators, this may mean that:

- their commitment to the reporting of hazards is actively promoted and they take extra care to ensure they have clear policies that encourage hazard reporting;

- they normalise the data they receive to fully understand the reporting rate and issues raised during reduced operations (e.g. look at rates against number of flights or specific routes rather than just numbers of events or reports).

- they review their safety performance indicators to make sure they are still appropriate for the extent of the operation that is now being conducted.

Managing risks associated with fitness-for-duty

Fitness-for-duty is an essential part of a flight crew members' responsibilities. The airline can support flight crew to manage their fitness-for-duty by having a clear and published policy, so that crew know what to report and how they will be treated if they need to report any such issues. The policy should recognise:

- Any requirements related to no-fly periods following flight crew being vaccinated;

- The organisation's training programs that include topics of fitness for duty in the operator's training program, and that clearly identify the responsibilities of the individual employee and of management. In COVID-impacted conditions, refresher training on the fitness-for-duty policy and, where applicable the specific fatigue-reporting policy, may be warranted.

- The need for a fitness-for-duty conversation between all crew during the combined crew briefing. This may require an amended policy, enhanced procedures, or additional communications, including the potential for extra time for briefings.

- The operator's commitment to return flight crew members back to work through established processes, once deemed fit.

- The potential for compounding HP issues that may impact on fitness-for-duty, and how this should be managed.

- The need for crew members to consult their aviation medical examiner to clarify any concerns they may have regarding their fitness.

Addressing procedure-related issues

Managing change will be a constant challenge for airlines as the current situation remains dynamic. In particular, COVID-impacted conditions seem to have resulted in an almost perpetual need to amend or establish yet another procedure, often in very short periods of time. This presents the potential for unintended consequences and errors. To address procedure-related issues, operators are advised to:

- Ensure flight crew are kept up-to-date on the operator's COVID-Safety plan and on any new or amended procedures;

- Carry out a full assessment of wider changes in the organisation to consider flow-on effects of a procedural change, e.g. given that enroute diversion airports may be closed, limiting suitable emergency alternatives, operators may need to review fuel and alternate planning policies and the effects on contingency planning and their implementation by flight crew already working in a challenging work environment;

- Provide conservative procedures, allowing crew to take into consideration their currency, proficiency and familiarization with environment when managing adverse weather or similar risks;

- Anticipate longer transition periods for new procedures and establish a plan to monitor their adoption.

- Establish a return to work training programme or pre-return to work briefing for crew coming back into the operation (see next).

Establishing a return-to-work programme or pre-return-to-work briefing

Providing current information and guidance will be an important element in supporting flight crew as they come back into the operation. There are likely to be significant changes as they reintegrate back into daily operations. In particular, return-to-work programmes or briefings allows attention to be given to:

- Familiarization with COVID-19 procedures, including any requirements for no-fly periods following vaccinations;

- Any altered operational procedures, such as those related to contingency implementation;

- A review of the fitness-for-duty policy;

- the mechanisms in place to report any issues and encouragement of crew to speak up at any time, if they have any concerns.

- Addressing concerns around lack of normal operational practice and potential impacts of loss of confidence, and the mitigations available to address those concerns (see Returning to normal crew training, proficiency and recency validity periods);

- Promotion of peer to peer support programmes where flight crew concerns can be shared with colleagues.

4. Personal mitigations for crew

Flight crew can also use personal mitigations to address the additional challenges of operating in COVID-impacted conditions:

Conduct a self-assessment prior to return to operations

Pilots should consider an honest self-assessment of skill level during the return to operations. Pilots should be willing to accept that they may have a temporary reduction in their skill level due to a long lack of exposure and be able to put in place appropriate countermeasures. This may include making a conscious decision to use a conservative approach when managing in-flight threats, e.g. undertaking approaches in bad weather. For pilots that have never been away from an airplane for such an extended period of time, they may believe that they still have the same skill set that they previously had. If the pilot identifies that additional support would be beneficial, they should take advantage of any extended return to work training that may be offered by the operator.

Start duties well rested

While there are likely to be more stressors in the crew members home and work environments, prioritising enough good quality sleep is key to being fit for duty. Establishing and sticking to a healthy sleep routine, as well as scheduling time to be both physically and mentally active can help crew members better manage stress and fatigue. Access to public transport and potential for disruption to other forms of transport may increase stress on crew members and their ability to optimise their rest periods. This may mean minimizing commuting time and flight crew may elect to take rest accommodation closer to base. This can reduce the impact of time awake prior to reporting or enable a nap to be taken prior to driving home. Gaining the support of family members who recognise the importance of quality undisturbed sleep for flight crew members prior to duty often results in better protected sleep periods and can also assist in crew to be well rested.

Prepare with back-up nutrition packs

The entire world continues to operate in a dynamic environment with daily changes in COVID response plans, work schedules, and availability of nutrition and transportation. Crew members should plan for the unknown by bringing some of their own non-perishable food items, taking into account any food quarantine requirements, to support health and well-being not only when nutrition is unavailable, but also when food items do not support their dietary desires or needs. Having a personal plan in coordination with the crewmember's carrier can further avoid nutritional deficiencies which can contribute negatively to fitness for duty.

Seek appropriate support or medical management

Experiencing feelings of low wellbeing during COVID-impacted conditions is very common. Flight crew are not exempt from this, and should make use of peer support programmes or employee assistance programs where available. Asking for extra support is the best option in the long-run and does not automatically mean unfitness for work. By receiving advice and help early, it might mean that individuals can safely continue to work, or if they can't, then they will get back to work quicker in the long run. However, it is a flight crew member's responsibility to report mental or physical conditions that may affect their ability to perform to an acceptable level to maintain safe operations in both normal and abnormal conditions.

Use the organization's reporting systems

This current situation is unprecedented for everyone in the aviation system and this makes it even more important to report issues associated with safety to the operator. The day-to-day challenges and changes that crew face as they manage the safety of the operation maybe hidden from those within the organisation. Reporting issues not only supports your colleagues to understand where issues are arising but they also enable the operator to be able to track these issues and put in place mitigations or make changes to support the safety of the operation. Crew members are essential in reporting operational safety issues and mitigation planning.

5. What can States do?

States can:

- Provide appropriate guidance and support to aviation medical examiners to manage the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being and resulting fitness-for-duty issues in a consistent manner;

- Provide clear and timely communications to all stakeholders on the means to maintain licensing and proficiency to enable safe performance of duties;

- As part of their safety promotion activities, encourage operators to implement peer-support programs and provide guidance related to individual responsibilities for reporting health concerns to AMEs;

- As part of their surveillance activities, the civil aviation safety inspector should be looking to check that:

- There is a fitness for duty policy that is followed. This policy should identify when a flight crew member is considered "not fit for duty" as well as the method for reporting "not fit for duty" and the consequential organisational responses.

- The policy is consistently understood and applied at all levels of the organisation, crew, supervisory levels, and upper management.

- The operator's training programs address topics of fitness for duty (including those related to the use of drugs and alcohol, medical conditions, mental health and fatigue), and clearly identify the responsibilities of the individual employee and of management.

- The operator has and uses a process that encourages the voluntary reporting of hazards, including hazards to HP (e.g. fatigue-related hazards), that maintains confidentiality as appropriate.

- There is evidence that the operator monitors voluntary hazard reports and uses the information to ensure mitigations are working as expected as well as to inform its decision making.

- There is evidence of communication to crew members (individually or generally) of improvements made based on their reporting and suggestions.

- The operator's return-to-work programme details the specific operational challenges, with adjustments made to the training plan to meet any identified issues.

For further information on HP considerations for regulators, see the Manual on HP for Regulators (Doc 10151).

Aircraft

This section includes information related to storage of aircraft, disinfection of aircraft and returning aircraft to service.

Aircraft and equipment disinfection

Safety considerations for use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers in aircraft

Repurposing aircraft passenger cabins for transport of cargo

Airworthiness surveillance priorities

Cargo

Guidance in this section addresses the flight ops implications of cargo-related activities such as transporting vaccines requiring cold storage and transporting cargo in the passenger cabin.

Repurposing aircraft passenger cabins for the transport of cargo